Although Star Trek is broadly known for its idealism and optimistic approach to humanity’s future, there are moments when Gene Roddenberry’s vision was helmed by others that tested its limits. After his death in 1991, Rick Berman took over and plotted the franchise on a sometimes darker course with shows such as Deep Space Nine. In the end, the good guys win, but Gene’s utopia contended with complex issues such as intergalactic war, more tension among the crew, and let’s not forget Section 31, a secret arm of Starfleet Intelligence that isn’t morally bound in its execution of protecting the institution.

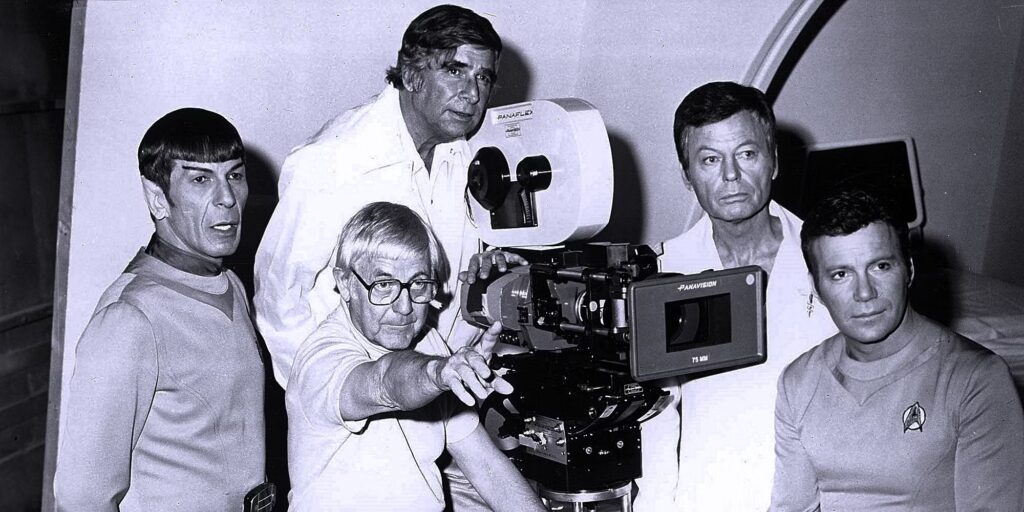

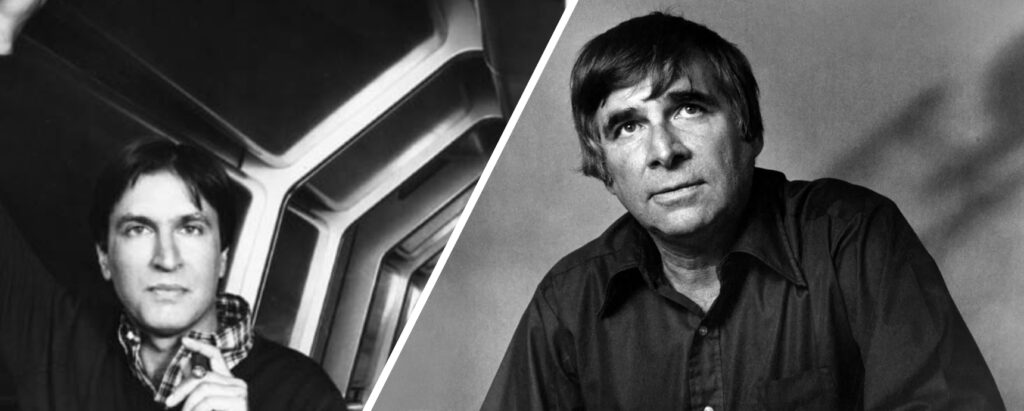

Based on the financial success of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Paramount (logically) made more ST feature films. However, despite the first film’s impressive box-office numbers, it didn’t resonate as well among critics and some fans. The production was plagued with costs skyrocketing to new levels while script changes were approved by the hour. With a final budget of 44 million dollars, ST: TMP was at the time the most expensive picture ever made. Gene’s original pitch for a sequel was a bit bonkers, the crew time traveling to prevent the assassination of JFK. Consequently, Gene was essentially demoted to “Executive Consultant”, as the studio placed TV producer Harve Bennett in charge of the next few films; enter one young writer and director Nicholas Meyer who was tasked with delivering a film on a limited budget (11.8 million) and a very tight schedule. The studio had already booked Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan for a June 1982 theatrical release without a completed first draft of the script!

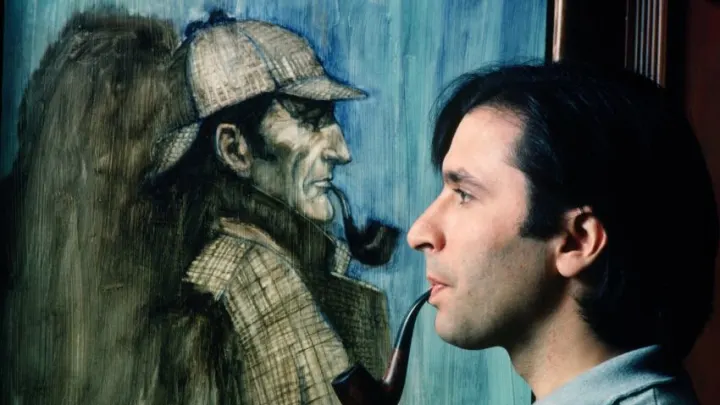

Over the years, Meyer has been linked with saving the franchise, breathing new life into it, thus opening the doors for how we regard ST today. He wrote the Sherlock Holmes-based novel, “The Seven-Per-Cent Solution” (published in 1974) and directed 1979’s critically acclaimed Time After Time. Although STII and the other films he wrote ( Acts II & III of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home) or directed, (Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country) were well-received and profitable, Roddenberry was not always on the same page. It’s understandable when you account for the natural tendency to be protective of your life’s work. Further, these are two different men with contrasting outlooks. However, this tension was vital in keeping ST grounded, while expanding its universe and quite frankly, keeping it relevant long after the original show’s broadcast was canceled in 1969.

I recall an L.A. Times interview with Meyer in the early 1990s, where I roughly quote, “The omens don’t look good”, regarding the hole in the ozone back then. As a teenager, that was my first glimpse into his tendency to be candid. It’s not to say that Meyer is confined to a belief that resides in the depths of utter despair or that humanity shouldn’t try. After all, in his stories, the protagonists confront incredible obstacles, much like how we’re collectively faced with our various existential problems. What’s different is an informed approach with respect to the historical precedent that shows in his writing and directing – Meyer is known for his interest in history and literature. It’s pragmatic futurism that we see in his version of the ST universe. Could this be based on logic rather than fantasy?

Roddenberry served as producer for the first film, a story that attempted to ascend into philosophical realms that may have lost a few people. Its cerebral quality revisited an area (“The Cage) previously rejected by the industry. Personally, despite its pacing and uniforms, I have grown to appreciate ST: TMP’s attempt at bringing us to the edge of our imaginations. However, it may not have been executed as masterfully as in 1969’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, 2014’s Interstellar, or 1997’s Contact starring Jodie Foster. Science fiction has always teased us about possibilities, but a fine line is walked when we endeavor into more “abstract” territory, at least when depicted in film: It is a tricky medium. The strength of ST: TMP is it’s still visually very potent, but the rest is mired in a dull script when compared to the other entries. Still, some lessons were learned from the first film that would better serve what followed.

I can only imagine how attached Gene must have been during the resurrection of his beloved franchise and throughout the first six films. This is the first contrast between him and Meyer, the latter who came into ST without ever seeing a single episode. It may have been his initial detachment that would prove to be useful. Meyer had mentioned before “playing it cool”, as one pulls the strings of a production. His philosophy as discussed in the podcast, The D-Con Camber is to see the job through, despite the emotional implications of a scene or even project. Take directing Spock’s death for example, where members of the film crew were crying while the scene was shot. Meyer was inclined to not break character, a term usually reserved for actors, but in this case, he fulfilled as a director. In time, he would grow to understand the appeal of Trek and its camaraderie, further grasping how those on set could react as they did to Spock’s death. Would Meyer himself have wept if Spock was killed later in STVI after embracing the franchise and making some friends? Somehow, I still doubt it and that’s an asset.

While ST is widely regarded for its core values, Meyer saw Starfleet’s role in the original series as exercising “gunboat diplomacy” (i.e. U.S. history and the Anglo-Saxons) in its affairs with alien races, as described in his book, The View From the Bridge. The Klingons are not only the adversary, but also the inferior race. Humanity imposes its values on other races, while (rightfully or not) claiming the moral high ground. It’s a matter of perspective, but it’s an observation worth noting given the historical context that Meyer tends to cite. For the record, I still lean closer to how Roddenberry wanted the Federation to be perceived, as ST is a work of fiction, thus I’m guided by the originator’s intent. I think we forget about intent sometimes and get carried away with our own notions. However, art is always left to interpretation. With that said, Daniel LaRusso is still not the bad guy in the first Karate Kid film if you catch my drift.

Meyer clashed with Gene on numerous occasions during the production of these films. Before photography began on STVI there was a meeting between them where Meyer asked for historical evidence that humanity would overcome its savagery, namely bigotry which was a theme in STVI. At this point, Gene was suffering from old age and illness, maybe thinking about his legacy and if it was in good hands for its final big-screen adventure to feature all seven of the original cast. Ultimately, Meyer stuck to his guns about certain details of the film’s story and script but would later feel guilty about the barely veiled hostility exchanged between their two parties.

Gene took issue with Admiral Cartwright, (a Starfleet Admiral) being a co-conspirator in the plot to sabotage peace with the Klingons along with the racism expressed by the crew of the Enterprise, namely Captain Kirk [“Let them die.”]. However, a compelling sub-plot of the film was having Kirk confront his prejudice, despite his son being murdered by the Klingons in Star Trek III. In my view, it’s a win-win when you account for the character’s evolution, as the beloved Kirk confronted feelings that are very real in today’s world. It’s a development where we see Meyer’s treatment of the captain starting somewhere closer to our reality and transcending (perhaps) towards Gene’s vision: Kirk is eventually enlightened and also admits his fear of change. Hooray, universal peace is achieved.

“You get into interesting philosophical waters, because Gene Roddenberry, the creator of all this, believed very much in the evolutionary perfectibility of man. And I don’t. Do you really think that we could weep over Romeo and Juliet or the plight of Oedipus if in fact we were not exactly the same people as those people? I don’t think we’re gonna change. We’re just gonna keep on trying to be better. The thing that dignifies us as human beings is not our accomplishments so much as our efforts. We strive. And that’s what Kirk is trying to do. Kirk learns about his prejudices. What’s the theme of this movie?” ~N. Meyer in an L.A. Times interview, Dec. 17, 1991

Roddenberry, once a policeman, perhaps always a policeman in a sense (as Meyer jokes in his book), had reservations from the start when he was hired for STII beginning with the death of Spock. These were essentially Gene’s children who were taken away from him by Paramount, so it’s understandable how killing off a main character would be a blow to any creator. But, perhaps it was how Spock was killed off that took the film’s conclusion to new heights; a death that was anything but unceremonious and now regarded as one of the franchise’s finest moments. Of course, we know what happens next, so with a few pick-ups and reshoots the door was opened for “life from death” i.e. STIII. Meyer did not agree with the extra footage being shot, as he stood firm on Spock’s sacrifice being final. The studio decided to leave the door open, as the success and praise of STII could only mean the well was far from dry.

The Wrath of Khan would introduce the famous Monster Maroon uniforms, replacing the pastel “pajamas” from the previous installment. The look of Starfleet took on a more militaristic aesthetic, pleasing to the eye, but once again going against what Gene intended for the Federation. Then again, this was the 1980s during Reagan in America, so something could be said about that too. Interestingly, this is an area where Gene and Meyer’s differences are intertwined with what they did agree on. Gene was a fan of Captain Horatio Hornblower, so the influence doesn’t escape anyone familiar with the material.

While Meyer was initially tasked to catch up on his understanding of ST, Captain Hornblower eventually came to mind. From there, he had the ball and would run with his own ideas: STII, a submarine battle in space. Ethan Peck’s grandfather, Gregory Peck starred in the 1951 film, Captain Horatio Hornblower. The British Naval uniforms of the Napoleonic Wars, (early 1800’s) that are featured in the film bear some resemblance to what we see in the uniforms in STII–VI. They are some of the most ornate and decorated uniforms in ST, complete with a clasp that secures a foldable lapel. They’re very dignified in appearance and exude a degree of that old-fashioned regal quality. The irony with how Hornblower was the common ground between these two men is not lost on me. Meyer just took it a step further by adapting not only the adventures of Hornblower but the look as well, at least in style and attitude. I would also mention that you can hear it in James Horner’s score for STII where it feels nautically inspired.

Nicholas Meyer was put into a position to (as he put it), “kissing the ring”; getting the blessing from ST’s creator, even if it was only a formality. – The real decisions were made by others. A final blessing was given, as STVI was viewed and liked by Gene three days before his death in October of 1991. Meyer fought for a simpler dedication at the beginning of the film, [“For Gene Roddenberry”], convinced that it would be more poignant, as opposed to something lengthy and flowery. I think Meyer made the right call there: Less is more. Sadly, there was no official reconciliation between the two, so Gene’s death may have only added to the aforementioned guilt Meyer carried with him. STVI opened on December 6, 1991, to a robust box-office weekend with favorable reviews; the icing on top of what was coined as a 25th-anniversary feature and the final outing of the entire original cast. This is the way Paramount wanted the original cast to go, as opposed to the lackluster critical and box-office results of STV from over two years before. From here, the torch could be safely passed with dignity.

Although, Roddenberry had lost significant influence on the flourishing series of ST films after ST: TMP, he was given full creative control in Star Trek: The Next Generation. Lightening had struck twice and that is a rare occurrence in Hollywood. We see a return to some of the themes from the original series while opening up the franchise to more possibilities. Gene’s touch is especially felt during the earlier seasons of TNG. While a return to television enabled Trek to revisit its roots, the films were generally geared toward a wider audience, so therein lies the balance of pleasing the fans while entertaining the public at large. That’s what made the charming STIV the most successful ST film (at the time), as it had crossover appeal.

Ten years after STVI, the world witnessed the horrors of 9/11, an event that dramatically changed the calculus of threats to society and the world abroad. Overnight, we transitioned from remnants of The Cold War into Global Terrorism, the latter a symptom of certain issues that had been brewing for a long time and now manifesting in unimaginable ways. The film that addressed the collapse of the Soviet Union (the Klingon Empire) and how the United States would respond (the Federation), painted a fairly optimistic view of the possibilities of two powerful entities coming together. In hindsight, that treatment and notion of how the world could take one step closer to lasting peace was short-lived, given the domestic and global events of the last thirty years. This is something that even Meyer has had to contend with, more shocking than when he was dismayed at discovering that Frank Capra was a Republican.

Although Gene’s role during the movies was marginalized, this was the universe he created. He was the one to revolutionize the genre of science fiction by simply bringing into it what made other types of programs and films compelling. He injected the essential elements of drama, storytelling, and character development, attributes beyond your typical monster of the week with no real motivation. Take the Horta from Devil In the Dark for example. Part of this legacy is the curiosity that ST sparks, something that had been lacking in the genre before the series premiered.

This article could be seen as an exposition on two philosophies intersecting. Sometimes matters became acrimonious, but evident that one could not exist without the other. There would be no franchise without Roddenberry as there would be no STII, IV, and VI, (as we know it) without Meyer. Nick would later go on to serve as a consulting producer on Star Trek: Discovery.

The story of Meyer’s contributions is a lesson in how dichotomy can be the springboard for reinvention, or at the very least an opportunity to explore other themes in the case of ST. Imagine how the Star Wars prequels would have been had George Lucas not returned to directing? Would they have been better films? Irvin Kirshner can largely be credited with the appeal of The Empire Strikes Back (*mic drop). Or imagine Lincoln’s cabinet filled with only yes men, which Lucas seemed very comfortable within. I digress, but you get the point.

Nick Meyer is credited with bridging the gap between utopia and situations that reflect the current times, as the original series cleverly did. – ST is always at its best when it is allegorical. He enjoyed making the films he wanted to make before a time when studios became overly concerned with what fans wanted to see, Rotten Tomatoes, and bottom lines that now dictate just about everything. Meyer’s handling of Roddenberry’s vision is intelligent and utilizes humor at the right moments, resonating even with people who do not consider themselves “fans”. It’s the work of a once dispassionate outsider who delivered this level of science fiction, as opposed to an acolyte that would completely shadow Gene’s preferences or cow-tow to other pressures, although some battles in this business are inevitably lost on all sides. I don’t mean this as a rub on Roddenberry at all. I think the lesson is knowing when to break away from dogma and when you play it “by the book”.

The idea of bringing ST from television to the silver screen is a feat rarely achieved with this much-enduring success. We can look at Trek’s origins as seeds that originated in one pot and were eventually transplanted to a garden (insert “garden spot on Ceti-Alpha VI” joke). As decades have demonstrated, the franchise is helmed by temporary custodians; caretakers who oversee each new endeavor, be it film, television, streaming, books, and so on. There’s no doubt that Gene’s influence is infinite, as it should be, otherwise we cannot call it Star Trek. I air on the side of the glass is half full when evaluating the disagreements among those who take this storied franchise into the next chapter. It’s a discourse that enables us to show our cards and make the hard decisions, whether we are the victors or on the side forced to concede. In the end, between Gene and Nick, I’ll offer a familiar phrase, “The Best of Both Worlds”.

*You can read further about Nicholas Meyer in his book, “The View From the Bridge”. I highly recommend it, as it was one of the sources for this article. https://www.nicholas-meyer.com/the-view-from-the-bridge

Also, please support Dominic Keating and Connor Trinneer’s show, “The D-Con Chamber“!

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-12-17-ca-500-story.html

0 Comments